Published on

Author

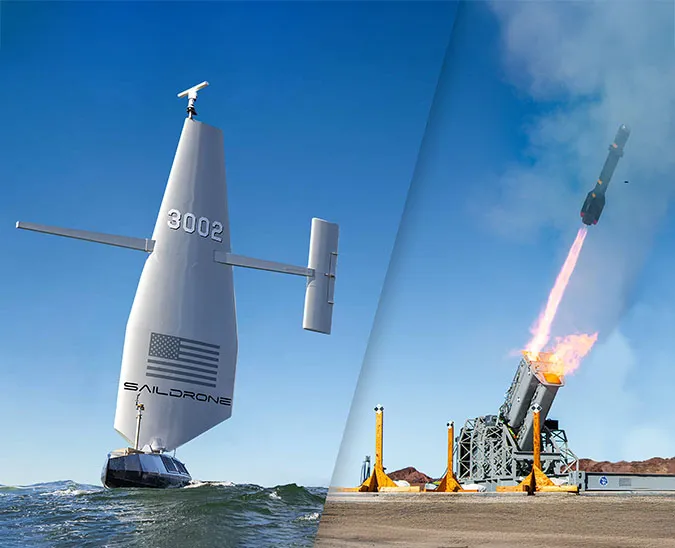

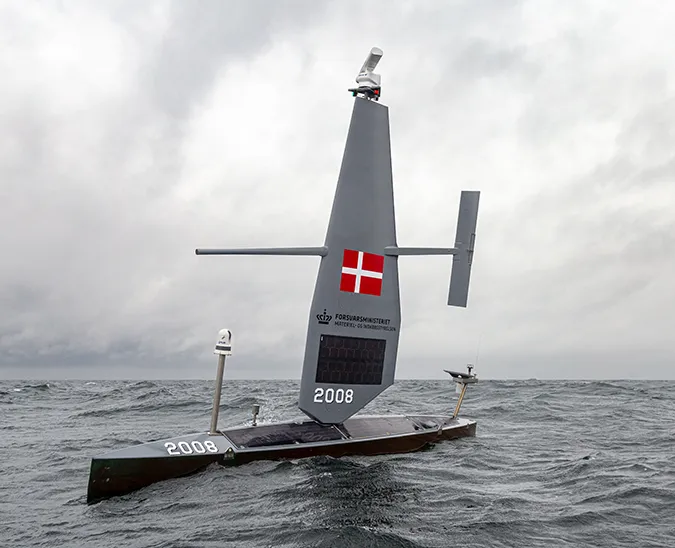

The Antarctic fur seal is one of eight species of southern fur seal. Commercial sealing nearly wiped out the Antarctic fur seal population in the 18th and 19th centuries, but today it’s thought to include more than four million animals. However, changes in the Antarctic ecosystem could impact the fur seals’ food supply, potentially affecting the health of the population. During the 2019 Saildrone Antarctic Mission, unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) equipped with echo sounders will attempt to track fur seals tagged with GPS locators and survey available food supplies to evaluate the effects of environmental changes in the region.

Fur seals can grow to be up to two meters long (6.5 feet) and weigh over 200 kilograms (440 pounds), though southern fur seals tend to be smaller than their northern fur seal cousins. While they breathe air, they often stay at sea for weeks at a time. They’re excellent swimmers and divers: Most foraging dives last about four minutes and reach a depth of 30 meters (98 feet). The known record for an Antarctic fur seal dive is 180 meters (590 feet) and the longest known dive is about 10 minutes!

Krill makes up nearly all of the Antarctic fur seal diet. A single animal can eat a ton—literally—of krill each year. That’s 440,000 pounds of the small, shrimp-like crustacean. They also like to snack on fish, squid, and seabirds.

When it’s time to breed, Antarctic fur seals return to the place of their birth. There are fur seal rookeries on several islands within the Antarctic convergence zone, which generally lies approximately between 45°S – 55°S.

One of the largest rookeries is on South Georgia Island. Located 1,200 nautical miles southeast of Cape Horn, it’s an inhospitable place for humans regularly pummeled by violent storms, but a paradise for fur seals, penguins, and other seabirds. The island’s only land mammals are reindeer, brought from Norway to feed hungry whalers, and the rats who hitched a ride—predators for the seabirds but not so much for the fur seals.

Fur seals practice an income breeding strategy, which means that all the resources a mother needs to give birth and raise her young pup have to be available in or nearby the breeding area. Once the pup is born, the mother will head out to sea to forage for food and return to feed the pup. If the availability of nourishment (krill and fish) changes, either by relocation or if there is less available, it makes survival more difficult—the mothers will stay longer at sea to find sufficient food, which leaves the pup vulnerable.

The Antarctic convergence zone is rich in krill, due to the upwelling of nutrient-dense water from the deep sea. Krill feed off the algae that live on the underside of the ice shelf; changes to the ice pack due to rapid warming can affect krill density. Ocean acidification, which is caused by increased amounts of carbon in the water, also presents a threat to krill populations, and in turn, species like fur seals and other marine mammals that rely on krill for food.

“Fur seals give us a really good idea of a specific area of use and how that area is changing,” explained Dr. Carey Kuhn, an ecologist at NOAA Fisheries Marine Mammal Laboratory. “Other animals like large whales migrate. They move through an area covering large distances, so it’s harder to tease apart what the resources look like over time.”

Bring Antarctica to the classroom

The 2019 Antarctica Circumnavigation is an education outreach initiative that uses cutting-edge Saildrone technology to bring data-driven lessons to the classroom. Saildrone and the 1851 Trust have developed a series of lesson plans rooted in science, technology, engineering, and math. The lessons are presented in three modules related to three areas of focus of the Antarctica Circumnavigation: Antarctic krill, food chains, and food webs, the carbon cycle and ocean acidification, and penguins as an indicator of a changing climate.

Read science-focused blog posts at saildrone.com/missions/antarctica or download the lessons at saildrone.com/missions/antarctica-lesson-plans

Resources

British Antarctic Survey, “Major impact of climate change on Antarctic fur seals,” ScienceDaily, July 23, 2014

I. L. Boyd, J. P. Y. Arnould, T. Barton, and J. P. Croxall, “Foraging Behaviour of Antarctic Fur Seals During Periods of Contrasting Prey Abundance,”Journal of Animal Ecology 63, no. 3 (1994)

I. L. Boyd, D. McCafferty, K. Reid, R. Taylor, and T. Walker, “Dispersal of male and female Antarctic seals (Arctocephalus gazella),” Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 55, (1998)