Published on

Author

To date, societal emissions of climate-warming carbon dioxide (CO2) have risen year-on-year since the mid-1800s. Over this period, the ocean has absorbed about one third of the emitted CO2 pollution. Now, we are at a global turning point, where much of society has agreed to take steps to avert the worst harms of global warming by drastically slowing—and eventually stopping—the addition of CO2 to the atmosphere. What methods do we have to check whether we are achieving this mission? And what role will the ocean play in future climate mitigation efforts?

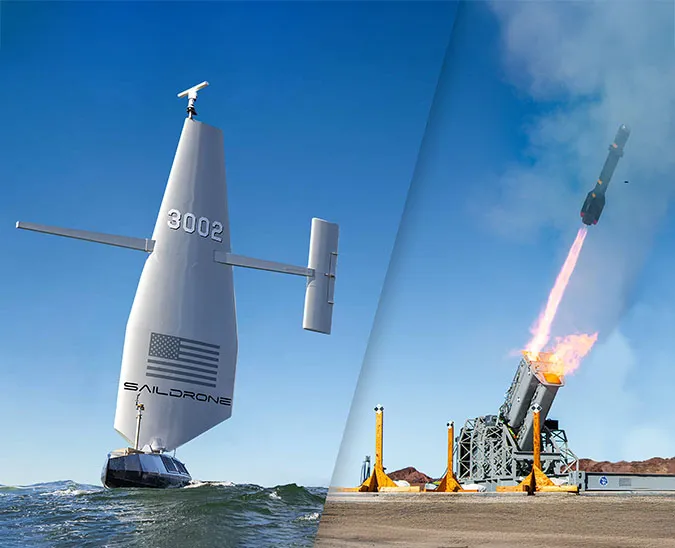

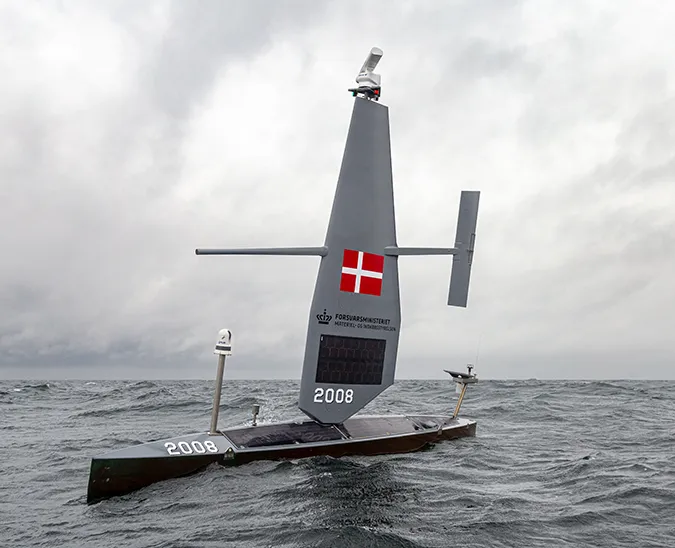

Ocean observing, including technological advances in persistent ocean platforms like those provided by Saildrone, is at the heart of addressing these questions. To understand progress towards the goal of climate mitigation, oceanographers are seeking more accurate accounting of the ocean’s CO2 uptake and storage. This task is critical for closing the global carbon budget—in which estimates of CO2 emissions are equal to the sum of atmosphere, ocean, and land carbon uptake.

So far, incomplete knowledge leads to uncertainties in ocean carbon uptake that are as large as the pledged emissions reductions over the next 10 years. In other words, we currently lack an observing system capable of verifying the global effort at emissions reductions. Even artificial intelligence applications seem to have “hit a wall” in narrowing regional uncertainties when trained with existing observations. We need more and better observations of the sea surface.

Our science teams have partnered with Saildrone engineers and pilots to advance ocean observing by making measurements in some of the most remote and challenging regions on Earth. From the first autonomous circumnavigation of Antarctica, to the very near-shore waters around Hawaii, to a wintertime multi-saildrone mission in the Gulf Stream, these partnerships are proving that autonomous surface vehicles can fill the most stubborn gaps in historical observing capabilities. We believe that a strategic, enhanced presence across more of the world ocean will allow us to better close the carbon budget and more accurately forecast the future role of the ocean in moderating climate change.

Recently, our quest to narrow the uncertainty on ocean carbon uptake started taking on an additional urgency. On top of the ocean’s role as a natural CO2 sponge for humankind’s pollution, there is growing interest in developing technologies to boost ocean carbon storage as a climate solution. In this context, it becomes even more critical to have a solid baseline knowledge of ocean carbon and a way to verify the success or failure of future efforts to scale-up ocean carbon storage. Saildrone USVs also provide a tool for the measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of ocean carbon dioxide capture pilot studies.

With deep engagement from the oceanographic community, and strong relationships with partner organizations like Saildrone, we can co-develop the ocean observing network needed to both verify climate mitigation efforts and see our collective future more clearly.

Saildrone is a proud member of the Friends of United Nations World Oceans Day. Learn more about the 2023 theme Planet Ocean: Tides Are Changing at unworldoceansday.org.

Support our vision of a healthy ocean and a safe, sustainable planet—follow us or join our team!

About the Authors

Jaime B. Palter is an associate professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island. She studies ocean circulation and biogeochemistry, focusing on the transport of heat, carbon, and oxygen through the ocean and across the air-sea interface. To do this, she collects new observations with moored and autonomous platforms, including Saildrone Explorers and Seagliders, and combines them with thee vast archives of historical hydrographic and satellite data. She has recently become involved in the scientific assessment of marine carbon dioxide removal through enhancing ocean alkalinity, which has led her to pursue projects at smaller scales, closer to the coastline. She has served on the Scientific Steering Committee of the US Ocean Carbon Biogeochemistry program.

Christopher L. Sabine is the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa interim Vice Provost for Research and Scholarship and a full professor in the Oceanography Department. He received his PhD. in chemical oceanography from UHM in 1992. Since that time, he has published over 160 journal articles and book chapters on carbon cycling, climate change, and ocean acidification. His current research focuses on understanding the global carbon cycle, the role of the ocean in absorbing CO2 released from human activity, and ocean acidification. He has been a scientific advisor for a number of national carbon programs in the US and internationally. He has won several awards including the US Department of Commerce Gold Medal Award for pioneering research leading to the discovery of increased acidification in the world’s oceans and was recognized by the Intergovernmental Program on Climate Change (IPCC) for his contributions to the IPCC when they were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.

Adrienne Sutton is an oceanographer at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL) and affiliate assistant professor at the University of Washington’s School of Oceanography. Her research focuses on advancing our understanding of the ocean carbon cycle and how it is changing over time. Her team maintains nearly 40 moored autonomous time series around the globe that track air-sea CO2 exchange and ocean acidification. Adrienne also collaborates with engineers on observing technology development, leading to the first autonomous circumnavigation of Antarctica in 2019 and the transfer of autonomous air-sea pCO2 observing technology to industry and nonprofit partners. She serves on several international ocean observing committees, including the International Ocean Carbon Coordination Project and the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON). Prior to starting her career at PMEL, she spent three years at NOAA headquarters engaging the US Congress on issues concerning oceans and climate, which instilled her commitment to effective science communication that equips society to face the challenges associated with global change.