Published on

Author

In 2019, Antarctic exploration is difficult: Ships must cross the turbulent Southern Ocean facing violent storms, plunging temperatures, aggressive ice flows, and extended periods of darkness, not to mention the daily expense of running a modern research vessel. But imagine the early days of Antarctic exploration, when ships were smaller and slower, powered by wind or steam, food had to be provisioned for months at sea, often in the form of live animals taken onboard, warm clothing consisted of thick burlap or fur, and navigation was governed by the stars.

Despite the challenges and hardships, dozens of expeditions were mounted to attempt to penetrate the ice flows in order to reach Terra Australis Incognita, the Unknown Southern Continent, from as early as the 1400s. Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 becoming the first known European to experience Antarctic cold. British explorer James Cook became the first to cross the Antarctic Circle in 1773 and reached a latitude of 71°S in January 1774, then sailed within 75 nautical miles of the Antarctic mainland. In 1820, Russian Imperial Navy Admirals Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev were the first to officially see and discover Antarctica. And in 1898, Belgian Adrien de Gerlache’s Belgica expedition was the first to spend an entire winter within the Antarctic Circle. It was also the first expedition to focus purely on scientific discovery.

De Gerlache had always been attracted by the sea. In his youth, he spent his holidays working as a young crew on the Red Star Line steamship making three voyages to the United States. Under pressure from his father, he enrolled at the Free University of Brussels to study engineering, but before graduating, he left the university to join the Belgian Navy, working his way up to captain.

The late 1800s are known as the beginning of the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration. De Gerlache learned of Swede Otto Nordenskjöld’s plan for an Antarctic expedition and wrote him a letter expressing interest in joining the voyage. When Nordenskjöld didn’t reply, de Gerlache began to plan his own expedition.

“[My grandfather] was convinced that polar exploration would be the final goal of our planet’s geographical discoveries,” explained Bernard de Gerlache. “It was as a naval officer with a serious scientific background that he embarked on the adventure of the Belgica.”

De Gerlache spent four years planning his expedition, purchasing a Norwegian-built sealer, the Patria renamed Belgica, refurbishing it with scientific laboratories, and recruiting a small team of sailors and scientists skilled in oceanography, meteorology, geography, anthropology, magnetism, biology, and the art of long-distance sailing. Young Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who later led the first expedition to reach the South Pole, served as first mate.

The Belgica, a three-masted barque with a 35-horsepower coal-powered steam engine (“Less than a small Zodiac circa 2000,” noted B. de Gerlache), sailed from Antwerp in August 1897 making stops in Madeira, Brazil, Uruguay, and Chile. En route to Antarctica, the Belgica made some 20 landings along the Antarctica peninsula, chartering and naming several islands. The Belgica crossed the Antarctic Circle on February 15, 1998. De Gerlache and the ship’s captain Georges Lecointe were well aware of the risks of pack ice but pressed forward as winter neared. Two weeks later, the Belgica became trapped in the Bellinghausen Sea, locked in the ice for 13 months.

“During preparations for the expedition, meteorologist Henryk Arctowski suggested the value of being the first to spend a winter in Antarctica to collect data and measurements over a full year. A plan for the construction of a small base out of wood on the Antarctica Peninsula was formulated,” explained B. de Gerlache.

Four members of the Belgica expedition were expected to spend the winter at Cape Adare on the north-easternmost peninsula of Victoria land; the rest of the expedition would sail toward Melbourne, Australia, while continuing to explore the Pacific Ocean, and return to Antarctica to retrieve the overwinterers the following summer.

Though the Belgica was underprepared to support the entire crew through the frigid Antarctic winter lacking food, clothing, and equipment to keep them comfortable and occupied—nearly all of the crew suffered from scurvy, and many went temporarily insane for lack of something to do—the expedition returned a vast array of scientific data and discoveries that led to 92 publications over 40 years. The data is stored at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and continues to serve as a wealth of information still consulted by scientists all over the world.

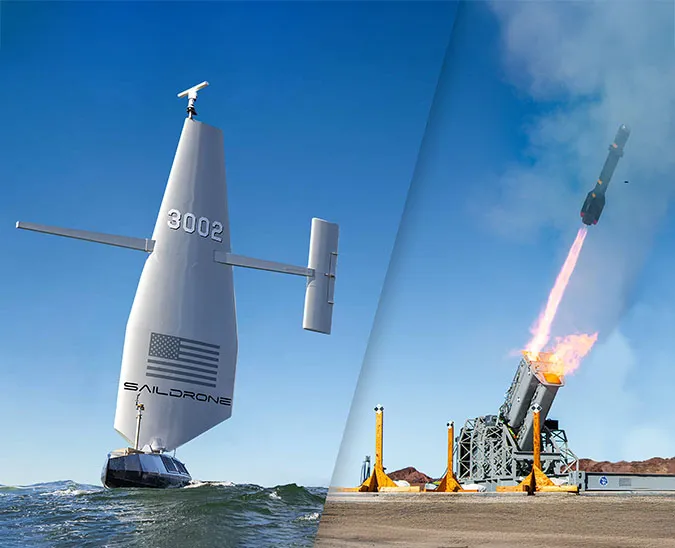

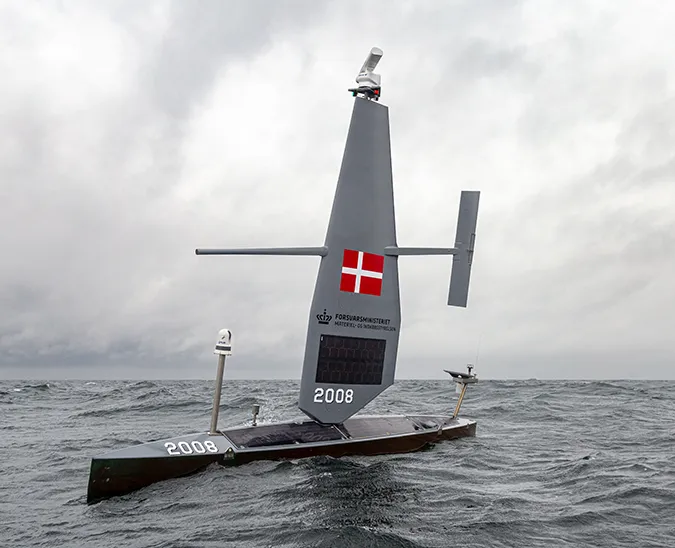

On January 19, 2019, Saildrone launched a custom-designed unmanned surface vehicle (USV) known as SD 1020 from Point Bluff, New Zealand, on a mission to complete the first autonomous circumnavigation of Antarctica some 120 years after the Belgica. During the 15,000 nautical mile journey, the SD 1020 collected valuable data on the marine ecosystem, meteorology, and CO2 absorption and emission in the Southern Ocean. The mission and the data collected will be used to teach students about the rapid changes taking place that affect the Antarctic ecosystem, and how this impacts humanity. The mission was completed on August 3, 2019.

The Belgica expedition was full of risks: Surviving the Antarctic winter following the long voyage from Belgium and the famous storms of the Southern Ocean—a terrifying prospect. The Saildrone USVs, even with the support of cutting-edge technology and design, face similar challenges in the harshest ocean environments in the world. But, as Adrien de Gerlache would say, “It must be done!”