Published on

Author

St. Paul Island, the largest of the four Pribilof Islands located in the Bering Sea not quite halfway between Alaska and Russia, is known for having the largest population of northern fur seals in the world (and 203 species of birds). But local fur seal populations have fallen 80% over the past five decades, and there is no immediate explanation for the decline. Scientists have been able to rule out the obvious causes—poaching, entanglement in marine debris, migration.

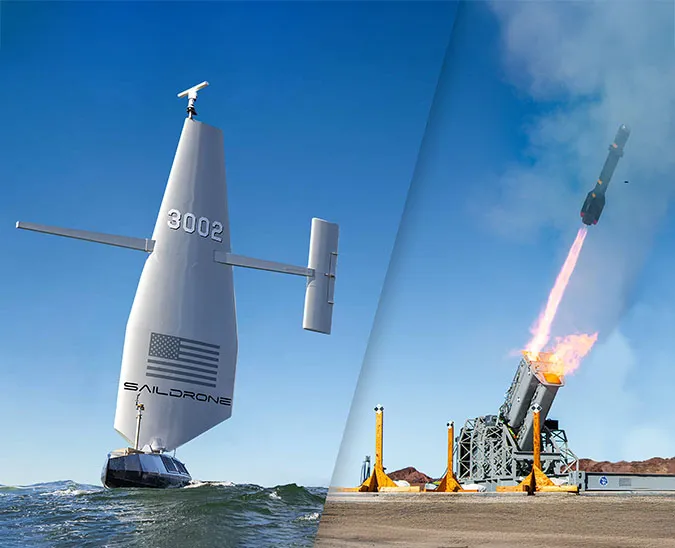

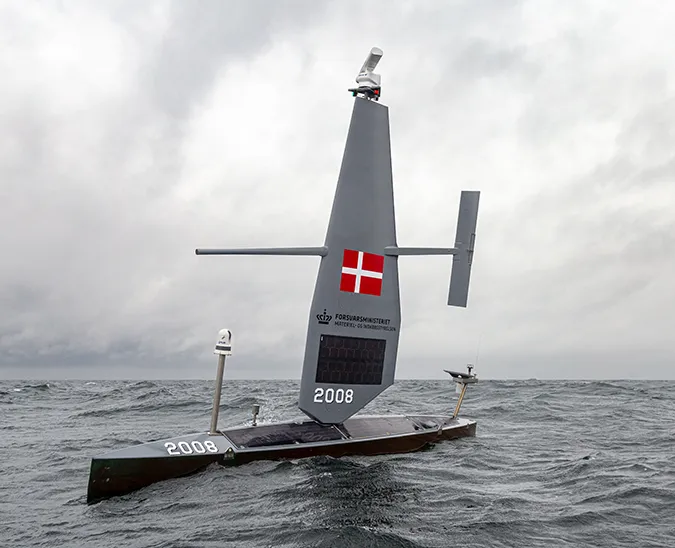

Critical information is needed about the relationship between fur seals and their prey—where it’s located, how much there is, and how that affects behavior and population. Data collected by Saildrone wind and solar-powered unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) is bringing scientists closer to understanding the mysterious disappearance of the Pribilof Islands fur seals.

“We’re pretty sure it’s not a single, straightforward answer. It’s probably interactions between multiple things,” said Dr. Carey Kuhn, an ecologist at NOAA Fisheries Marine Mammal Laboratory. Kuhn has been tracking northern fur seals for much of her career and is collaborating with Saildrone on research in the Bering Sea. Her paper, "Test of Unmanned Surface Vehicles to Conduct Remote Focal Follow Studies of a Marine Predator," was published by the Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Saildrone is working with NOAA Fisheries to survey fish stocks like walleye pollock, track northern fur seals, and locate right whales in the Bering Sea.

The native Unangan people were hunting seals on St. Paul for survival long before Russian fur hunter Gavrill Pribylov arrived on the island in 1786. Fur seal pelts were a valuable commodity in Europe and Asia, and a century of overhunting nearly wiped out the local population. The 1911 North Pacific Sealing Convention is the world’s first wildlife conservation treaty, designed to monitor the commercial harvest of northern fur seals and sea otters in the Bering Sea.

Fur seal populations increased sharply, reaching nearly 500,000 individuals born on St. Paul Island in 1940. The spectacle on St. Paul is astounding: Rookeries dot the remote island’s coast with thousands of fur seals coming ashore to breed each July. But despite the cacophony of bleating, barking, and groaning that takes place every summer, in 2018, only about 75,000 pups were born.

Fur seals spend the majority of their life at sea. Most female fur seals practice philopatry, that is, returning to the same spot an individual was born year after year to give birth. To feed their pups, mothers swim for days at a time to forage for food, diving up to 200 meters (600 feet) deep. Not only are fewer pups being born, but there are also fewer fur seals are returning to breed. Large numbers of northern fur seals are simply disappearing. Whatever is happening to the fur seal population is happening deep under the water, but the habits of the species present many challenges to large-scale observation.

Environmental factors like a temperature shift in the Bering Sea from colder to warmer, which began in the 1970s, favors leaner, less nutritious fish like walleye pollock and could be impacting the fur seal population. Pollock is known to be a primary source of nourishment for the northern fur seal, and also makes up America’s largest fishery, especially popular as McDonald’s fish sticks. US fishing vessels operating in the Eastern Bearing Sea have caught an average of 1.3 million tons of pollock annually since 1988. Warmer waters also push fish stocks further from shore, which means mothers must travel greater distances to find food for their young pups.

Because they’re an important commercial fish, pollock surveys are performed annually, but usually in June and July, before the fur seals arrive on St. Paul Island to breed. Fur seals rely on walleye pollock to feed their pups primarily from August to November. “To do another round of surveys later in the season would be so incredibly expensive. It requires large ships and researchers to analyze the data,” said Kuhn. “We had to assume that what we see in June and July represents all summer. It could have been a bad assumption, but that’s all we had.”

The 2016 Saildrone Bering Sea Mission, part of the Innovative Technology for Arctic Exploration (ITAE) program, aimed to untangle the impacts of climate variability and other environmental aspects on marine mammal populations. The goals of the mission included assessing the use of saildrones for acoustic fish surveys, observing the presence of the critically endangered North Pacific right whale, and examining the foraging behavior of fur seals in relation to the field of prey.

Two Saildrone USVs completed a 105-day, 12,075-kilometer (7,503-mile) mission to examine pollock distribution in a traditional foraging area. Saildrones are capable of sailing autonomously while carrying a suite of science sensors designed to collect a range of data without disturbing the ecology of the survey site. In the Bering Sea, the saildrones were equipped with customized active and passive acoustic sensors. A Simrad Wide-Band Autonomous Transceiver (WBAT) and keel-mounted gimbaled 70 kHz model ES70-18 CD transducer were used to estimate fish distributions; an Acousonde passive acoustic recorder captured marine mammal vocalizations.

The mission included 65 days tracking foraging fur seals, including several focal follows, during which the saildrones followed tagged animals for more than 80 hours and 210 kilometers (130.5 miles). The saildrones also rendezvoused with the NOAA research vessel Oscar Dyson to cross-compare the USV and ship sensors.

“The saildrone lets us go out and measure all of these fish—where they are, how much is available—when the seals need it. We can look at really specific relationships between where the seals are and what the fish look like. We don’t have to rely on assumptions that the data that was available a few months before is still valid. We get to tease apart the relationships in real time,” explained Kuhn.

Cameras attached to the backs of northern fur seals give scientists a better look at the animal's habits.

Kuhn says without a doubt, the mystery of the Pribilof Islands fur seals has not yet been solved, but the research is moving in the right direction. In addition to Saildrone fish stock assessments, her team has attached tiny video cameras to select seals to document what they are seeing and eating when they dive, which allows them to quantify an animal’s energy budget. The next step is to integrate the fish stock data with the observational seal cam data into larger models to understand how much fish a fur seal population requires versus the individual animals they’re following.

Results from the 2016 Saildrone Bering Sea Mission were presented in a paper published in Oceanography. NOAA published more information about this mission on the Science Blog.

Resources

Christine Baier, "Scientists are on the ground this month in the Pribilof Islands to recover groundbreaking fur seal data," NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center News, September 19, 2016

Calvin W. Mordy, Edward D. Cokelet, et al., "Advances in Ecosystem Research: Saildrone Surveys of Oceanography, Fish, and Marine Mammals in the Bering Sea," Oceanography, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2017

Carey E. Kuhn, Alex De Robertis, et al., "Test of Unmanned Surface Vehicles to Conduct Remote Focal Follow Studies of a Marine Predator," MEPS Vol. 635, 2020

"Unmanned Surface Vehicles Track Marine Mammals on Extended Foraging Trips for the First Time," NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center, February 19, 2020

"2018 Northern Fur Seal Pup Production and Adult Male Counts on the Pribilof Islands, Alaska," NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center, accessed March 13, 2019

Walleye Pollock Fact Sheet, NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center, accessed March 13, 2019